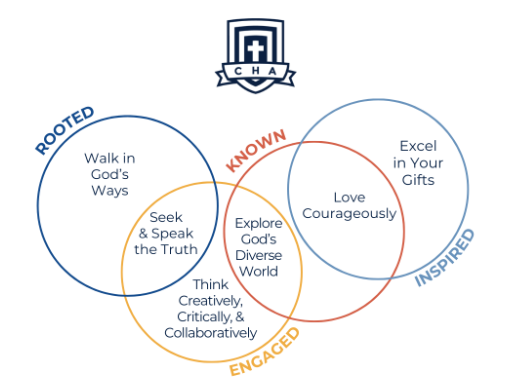

This past school year I’ve sought to clearly articulate CHA’s vision – that our students are rooted, known, engaged, and inspired through their experiences at CHA.

Articulating our vision is a really important step: if the members of our community don’t understand where we are going and why we are going there, how can we achieve anything of significance? But articulating a vision and making it happen aren’t the same thing. Articulation is only the first step. We also have to plan and we also have to do.

Much of the planning work done by the Board and our Administration is expressed in our Strategic Plan (Executive Summary found here). This goal-driven plan, especially in its full version, maps out year-by-year steps to achieve our stated goal, by God’s grace. And our Administration bases many of our annual goals on this strategic document.

But a school isn’t amazing because of administrative decisions like schedules and budget and org charts. Schools are amazing because of teachers and students and parents. It’s with these people that the rubber really meets the road. So how do each of those groups contribute to and participate in the vision – in getting us down that road?

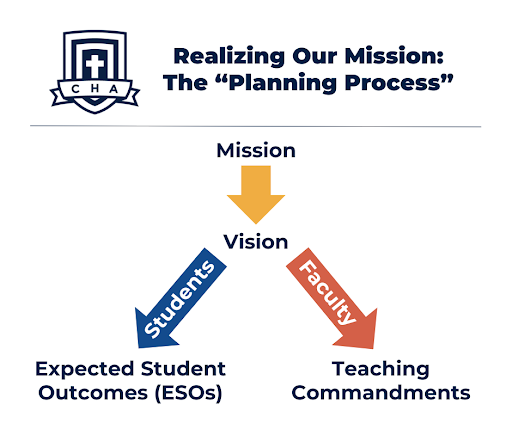

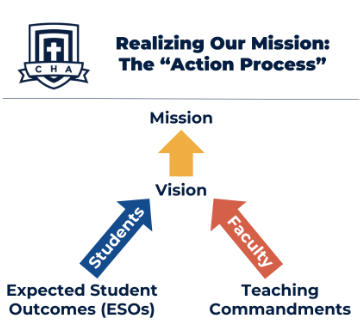

Let me provide a helpful visual that we’ve been using at faculty meetings:

The thing that drives our decision-making is the school’s mission – why we exist. Our Vision – the mission applied to this moment in our school’s history, is thoughtfully drawn from that mission. Likewise, our Expected Student Outcomes (ESOs) – what we pray will characterize our graduates, are drawn directly from that vision. See below:

Thus, and very importantly, if we challenge our students to work to be characterized by these six Outcomes throughout their time here at CHA, they will be participating in our school’s vision and, subsequently, its mission. This is why for three years we are deliberately working through one of our ESOs each semester in chapel, in Bible class, and in mentoring – all with the hope that by the time our students graduate, these outcomes will be on the tips of their tongues. Read more about this past year’s themes of Loving Courageously and Seeking and Speaking the Truth.

But what about our faculty? Are they also provided with guidance for how to achieve our vision and mission, or do we simply ask them to “do stuff that makes our vision happen?”

Perhaps less known to our parents is the fact that over the last three years we have been developing and discussing Twelve Teaching Commandments with our faculty, aimed toward equipping and inspiring our students in achieving our Expected Student Outcomes and, subsequently, our mission and vision.

Our professional development is oriented toward these Commandments. Our faculty evaluation meetings are based on these Commandments. Teacher goal development is rooted in these Commandments. As with Student Outcomes, our expectation here is that as faculty work toward these tangible ends, we will see our vision and mission come to fruition. This ‘action process’ (below) is the reverse of the ‘planning process’ (above):

Teaching Commandments

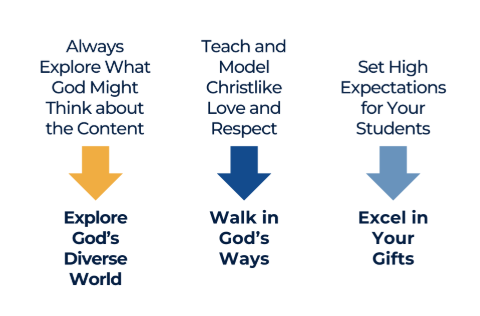

Let me provide a window for you into a few of our twelve Teaching Commandments. While six of the twelve are fairly standard elements of teaching (planning, technology, professionalism, etc.), the six below are somewhat unique to CHA and worth explicitly articulating because of their direct links to Student Outcomes:

1. Always Explore What God Might Think about the Content (Explore God’s Diverse World)

The reason I fell in love with literature – and eventually became a high school English teacher – was because of an author named T.S. Eliot. This quote, from his Four Quartets, used to always be on the wall in my classrooms:

“We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.”

I love this quote because it embodies the incredible and paradoxical reality of Christian education. The more we explore the world and its complexities and mysteries, the more we come to understand the most basic truth: that it all is His. All knowledge points to Him.

Another quote I love is a more recent one from this interview with MS/US faculty member, Sharon Ledbetter:

“One day one of my students said to me – an eighth grade student – ‘Mrs. Ledbetter, I noticed something. Every single conversation we have in class always comes back to Jesus or the Bible.’”

“And I said, ‘Well that’s not true. Because it never left Him in the first place.’”

I think T. S. Eliot would agree. At CHA our commitment is to look at every piece of content that we teach – every discussion that we have – as an opportunity to understand God and his world and his people.

Some time ago I was sitting in the back of Dr. Noell’s classroom listening to an Upper School discussion about the changing landscape of urban populations. There were a number of questions and a good deal of back-and-forth. And then Dr. Noell asked this: What are the practical implications of this data if you were seeking to tell people about the gospel in a city like this?

I don’t know what it’s called when your jaw drops and you smile at the same time, but that’s what happened to me. It was very hard not to quietly fist pump. The subsequent conversation was great. What were the different experiences of people in this urban context? How would you minister to them? Where would the difficulties be? How might God think about these demographic realities?

Our goal is that every classroom conversation – whether on urban demographics, hatching chicks in Dr. Oh’s First Grade class, or the dissection of owl pellets in fifth grade science – is an exploration of God’s world and, ultimately, what God might think about it. And the end of it all is to feel like we know him, again, for the first time.

2. Teach and Model Christlike Love and Respect (Walk in God’s Ways)

In addition to T. S. Eliot, another important piece of paper, prominently displayed above the center of my whiteboard, was a simple message: RESPECT. Loving respect is the foundation of a Christ-like learning environment.

Students must lovingly respect other students by listening, giving helpful feedback, asking genuine questions, and providing encouragement.

Students must lovingly respect their teacher by listening, being responsible in keeping up with the work, avoiding shortcuts or cheating, and asking questions in order to understand.

Teachers must lovingly respect their students by providing quality lessons, giving timely and helpful feedback, respecting curiosity and effort, and pushing students to fulfill their potential.

You cannot learn without being able to take a risk. And it’s incredibly hard to take a risk if you know you are surrounded by people who will mock and belittle your efforts, failing to treat you like someone made in the Image of God.

Our faculty strive to create an environment that models this kind of loving respect.

3. Set High Expectations for Students (Excel in Your Gifts)

Not too long ago I mentioned how interesting it is to explore the example of Jesus-as-teacher, looking at the pedagogy of Christ. One passage that stands out for this reason is John 21, where Jesus meets Peter after Peter’s denial and after Jesus’ death and resurrection.

Jesus’ approach is filled with the loving respect described above. Instead of berating or shaming Peter, he gives him the dignity of offering him breakfast. Instead of telling him what he did wrong (Peter certainly already knows what he did wrong!), Jesus asks him questions about what is next.

But something I really love about this passage is that because Jesus loves Peter and offers him dignity, he also has high expectations for him. Jesus does not back down from the potential he sees in Peter, on whom he plans to build his church (Mt 16:18). Despite Peter’s shortcomings, Jesus challenges him to feed his sheep. To lead. (Jn 21:17).

This is the Master Educator at work. Christ does not deny the reality of Peter’s failure. He treats Peter with dignity despite his failures and shortcomings. And because of his loving respect for Peter, he continues to challenge him to fulfill his potential. In the same way, our faculty seek to set high expectations, rooted in a respect for each student’s imago dei and God-given potential.

Growing up, I always got good grades. When I was in 8th grade, I decided to test the limits of how little I could do to get an A in my English class, so I turned in a short story I co-wrote with a friend of mine that was pretty ridiculous. The next week, my English teacher, Mrs. Kennedy, handed it back to me with a big fat F on the top and told me she wanted to see me at lunch. I sheepishly entered her classroom at lunch, red-faced and cotton-mouthed, half expecting my parents to be there, looking up at me through their eyebrows. But it was just Mrs. Kennedy, and her words had a profound impact on me: “Joey, you are an excellent writer. Do you think this was your best?” “No, Mrs. Kennedy.” “Joe, I’m going to give you two days to write me a really good story. I want you to know that God has given you a great mind, and I expect you to use it.”

That day after school I slammed out a killer story. I had never been more motivated to write. Why? Because Mrs. Kennedy respected me enough to expect great things from me. And she didn’t mock or belittle me for doing something dumb.

If a student cheats on a homework assignment, it’s a big deal because we respect his or her potential. If a student struggles on a test but did his or his best, we don’t want to lower the bar; we want to praise the effort. Our academic expectations and performance expectations are high. Why? Because we respect our students enough to push their limits. And we seek to do all this with grace and dignity and respect. Watering things down is not honoring; it is disrespectful to the God-given potential we see in our students.

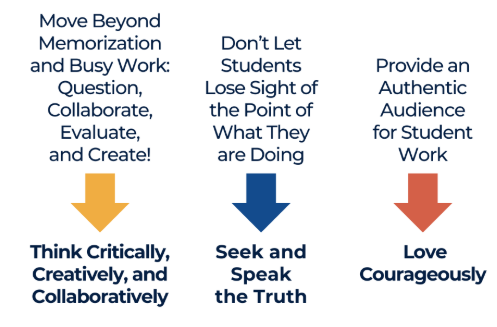

4. Move Beyond Memorization and Busy Work: Question, Collaborate, Evaluate, and Create!

(Think Critically, Creatively, and Collaboratively)

The word “education,” interestingly, comes from two Latin roots – educare and educere. The former has to do with “molding” or “training.” The latter denotes “drawing out.” (Maurice Craft, 1984) The latter denotes “drawing out.” This is particularly interesting because both roots represent two different approaches to education. The former engenders an approach similar to what many of us are used to – in which the teacher conveys knowledge to students, and they remember it and perform it. The latter is more student-centric wherein the students are presented with a problem or a phenomenon and asked to explore, explain, or re-create it.

Perhaps unusually, at CHA we value both. However, for years CHA has relied primarily on the former approach. But we are aiming to find the right balance, encouraging faculty to prepare students to dynamically engage with the material through questioning, collaboration, critical thinking, and creative expression.

In eighth grade English, our students write a research paper. But instead of a stuffy paper titled “The Causes of World War One” or “The Amazon Rainforest,” students must research a human rights injustice, rooted in a full quarter of discussion on two novels that address human rights abuses, explore what God might think about it, and propose a solution.

In fourth grade, our students don’t simply research a historical figure, they use their research to be a live exhibit in their living history museum.

Last semester I sat in on a wonderful discussion in junior biology after some incredibly thorough presentations on Young Earth Creationism, Evolutionary Creationism, and Intelligent Design. Students were not vigorously taking notes on a teacher presentation. They were giving the presentation and then discussing the biblical and scientific merits.

A question we regularly ask in our observations is: what are the students doing. Our goal, ultimately, is that students are the workers and teachers are the coaches and mentors in the learning process, ultimately serving to both ‘train up’ and ‘draw out’ students in their learning.

5. Don’t Let Students Lose Sight of the Point of What They are Doing (Seek and Speak the Truth)

Our faculty spent every Friday morning this past school year seeking to better CHA’s pursuit of this goal by developing Curriculum Guides. These Guides outline the core outcomes for every class at every grade level. Educational research is clear that for students to learn effectively, they need to have crystal clarity on what they are doing and why they are doing it.

Our goal is that at any moment, any observer can enter a classroom at CHA and ask a student “What are you learning” and “Why are you learning it?” and be given a solid answer.

We welcome the formerly-infamous student question, “Mrs. Johnson, why do we have to do this stuff anyway?!?!”

As students are able to articulate this, they are also able to understand that all learning is part of a Great Quest to understand God’s Truth and to be able to clearly articulate that Truth to others. Setting up learning in this way is foundational for our faculty.

6. Provide an Authentic Audience for Student Work (Love Courageously)

Something magical happens when we have to perform. I practiced piano furiously the days before my recitals. Why? Because I knew people would be watching. An audience demands excellence. And it is also the context of most vocational tasks. We argue a case before a jury. We present data to a committee. We triage to save a real life.

Academics should be no different. Providing an audience is fairly easy in athletics, in theater, and in music. It’s trickier in math or Bible, but we want to do what we can with presentations, portfolios, parent invitations, and publications to help our students to understand that learning isn’t just about knowledge but that it’s also about vocation. What you can do with what you know is where knowledge begins to be about loving others.

There is a quote in our GO! Week video that I love. Matty Chiong says, “We served Venezuelan refugees for one day, and there was definitely a little bit of a language barrier there, but I know some Spanish because I’m in Spanish class. It was really fun to see how my Spanish paid off!”

It’s not until you have an authentic audience that Spanish class becomes about loving others.

Our goal is for an authentic audience to be a regular part of CHA classes.

Hopefully that was a good glimpse into how our faculty, practically, seek to bring about our vision at CHA.

This year and next we’ll continue to unpack our remaining ESOs in this space, exploring how students also partake in our vision. But what about parents? What should parents do? Stay tuned!

—JT

.png&command_2=resize&height_2=85)